| Author | Ruru Ping (Graduate School of Economics, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo, Japan) Bo Hu (Care Policy and Evaluation Centre, London School of Economics, United Kingdom) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overview | The Long-Term Care system in mainland China is characterised by primary reliance on family caregiving, rapid growth of the residential care sector, underdeveloped home- and community-based services, and increasing involvement of the private sector. Recently, the central government launched an institutional reform to address the fragmentation within the LTC institutional framework and expanded the responsibilities of the Ministry of Civil Affairs. China has been piloting social LTC insurance in selected cities since 2016 and aims to develop a national social LTC insurance system in the future. Meanwhile, the government is implementing comprehensive systemic reforms with policy priorities focused on integrating healthcare and LTC sectors, strengthening home- and community-based care services, ensuring the provision of basic LTC services, especially for the disadvantaged older population, and enhancing the capacity of formal LTC workforce. Public LTC spending in China was estimated to account for approximately 0.02–0.04% of the gross domestic product (GDP) [1]. | |||||||||||||

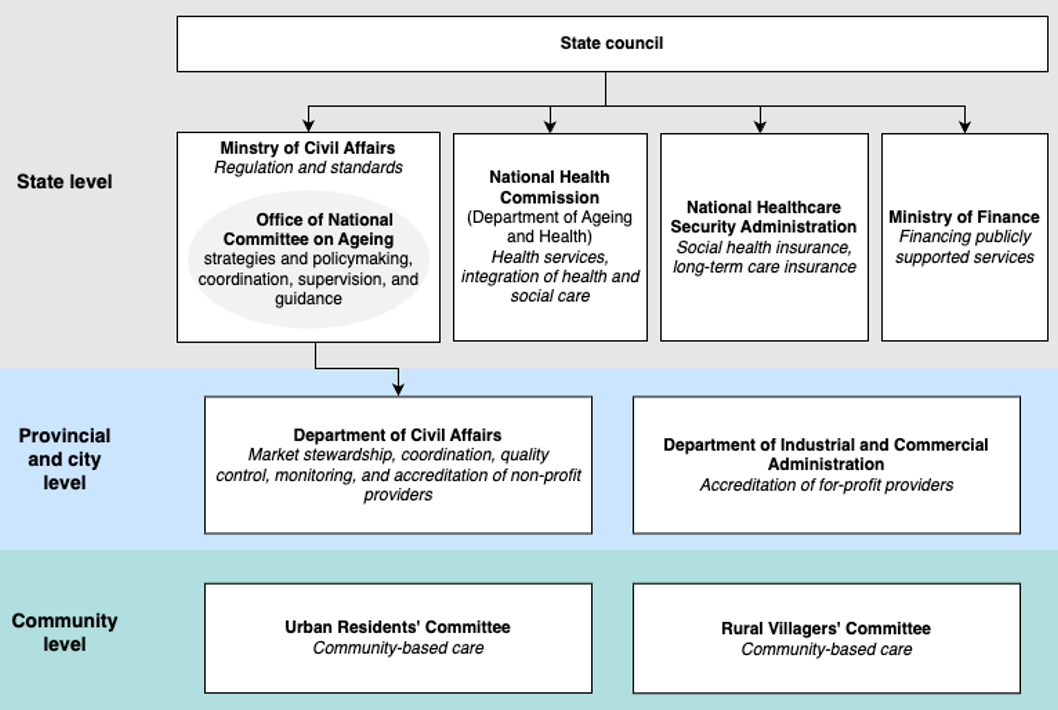

| Governance and system organisation | In mainland China, the Ministry of Civil Affairs (MoCA) serves as the key central government agency responsible for various aspects of the LTC system. Previously, the key responsibilities for LTC were shared among a variety of government agencies. In March 2023, the central government launched an institutional reform to address the fragmentation within the LTC institutional framework and expanded the responsibilities of the MoCA [2]. Following this reform, the Office of the National Committee on Ageing was relocated to the MoCA, further strengthening its roles in comprehensive coordination, supervision, guidance, and the organisation and promotion of ageing-related initiatives. Furthermore, the responsibilities previously held by the National Health Commission for organising, formulating, and coordinating the implementation of policies and measures to address population ageing has been transferred to the MoCA [2]. The National Committee on Ageing, established by the State Council, consists of 32 ministries, each represented by a vice-minister. The Committee formulates strategies and policies for care for older people, coordinates the relevant departments, guides the implementation of development plans, and oversees execution at local levels [1]. In addition, the MoCA functions as the national regulatory authority overseeing LTC services. It is responsible for setting regulations and standards, whilst actively engaging in the development of national training curricula and the accreditation of training programmes for LTC workers [2]. There are 34 provincial administrative regions in China, including 23 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, 4 municipalities directly under the central government and 2 special administrative regions. The 34 Provincial Departments of Civil Affairs (DoCA) are responsible for translating policies into practical measures at local level, following established laws and regulations. They establish guidelines for market entry and exit for LTC providers, ensure quality control and adherence to management standards, and impose sanctions on providers for violations or neglect of regulations [2]. Non-profit service providers are mandated to register with their local DoCA, while for-profit entities must register with the Industrial and Commercial Administration Department. Community organisations play an active role in providing LTC services. Many community-based services and programmes are either administrated by or delivered in collaboration with the Urban Residents’ Committees or the Rural Villagers’ Committees. Operating at the neighbourhood level, these Committees serve as quasi-governmental organisations, responsible for carrying out a range of administrative functions as mandated by the local government [2]. Several other ministries are involved in the LTC sector. Ministry of Finance is responsible for allocating financial resources to the development of publicly supported LTC services and setting prices for such services [2]. The Department of Ageing and Health at the National Health Commission is responsible for formulating policies, standards, and norms for the integration of health and social care [3]. Since its establishment in 2018, the National Healthcare Security Administration has played an instrumental role in exploring the establishment of a national LTC insurance system, particularly focusing on policy and standard systems, management methods, and operation mechanisms [4]. The LTC institutional setup in China is illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 1. LTC institutional setup in China

| |||||||||||||

| Financing and coverage | For the majority of older people in China, formal LTC is financed through out-of-pocket payments. Given the substantial costs associated with LTC in comparison to current retirement income levels, affordability becomes a significant concern for many older adults [5]. Although there are some subsidies for both LTC service providers and disadvantaged users, such as individuals aged 80 years old and above, those facing financial hardship, or disabled older individuals, and the central government has been piloting the implementation of LTC insurance since 2016, the adequacy of the subsidies for the disadvantaged population and the effectiveness of the LTC insurance pilots remain inconclusive. Public LTC spending in China was estimated to account for approximately 0.02–0.04% of the gross domestic product (GDP) [1]. Additionally, certain types of health related LTC spending for frail adults (e.g., health and nursing care, rehabilitation) are covered by the health insurance system and health budget, yet reliable estimates of these expenditures specifically attributed to LTC are not available [1]. Approximately 60% of total public LTC spending was funded by the central government from the Public Welfare Lottery Fund, while local governments contributed 25% of the expenditure, and the remaining 15% came from other resources [5]. Public financing for LTC encompasses subsidies for both service providers and users. On the supply side, these subsidies offer financial incentives for the development of residential care facilities, community centres, and other home- and community-based care services [5]. On the demand side, China is currently promoting the development of a subsidy system for older adults with special needs [6]. Local authorities have introduced old-age allowances for those aged 80 years old and above, subsidies for aged care services for those facing financial hardship, and nursing care subsidies for disabled older individuals. These subsidies are listed in the National Aged Care Services List released in May 2023. Despite these efforts, the impact of these measures remains insufficient in addressing the real consumption expenditures of older adults, particularly the “oldest old” population and those living with disabilities or dementia [7]. To improve the accessibility of formal LTC services for people in need and alleviate the caregiving burdens of family members, the Chinese government launched LTC insurance pilots in 15 cities and two provinces in 2016 [8]. The design of LTC insurance schemes varied across the pilot cities. The LTC insurance pilots were primarily financed through existing social health insurance schemes – the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI), which covers formal sector employees, and the Urban-Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URRBMI), which covers the rest of the population – by earmarking a particular percentage or fixed amount per person from the existing risk-pooled funds for LTC services [5]. All the pilots started by covering urban employees and retirees enrolled in UEBMI; some cities also cover URRBMI enrolees [5]. Some pilots also received supplemental funding from the governments, individuals, or employers [9]. Participation is voluntary [5]. Table 1 summarises more details on the design of source of funding and contribution mechanism. LTC insurance funds are administered at the municipal city level by local healthcare security bureaus, exhibiting considerable variations in financing, benefit levels, and operation status [10]. China has undergone a strategic shift in its policy direction. The government, previously acting as a direct service provider, has now transformed into the role of purchaser and regulator of services [1]. In pilot cities, the LTC insurance schemes, managed by local healthcare security bureaus, implement their respective purchasing mechanisms that procure care services and negotiates prices with providers on fixed costs [11,12]. Table 1. Summary of financing mechanisms in pilot cities (as of May 2023)

Source: Adapted based on [11] Eligibility is stringent. In most cities, individuals must be severely disabled for a minimum of six months, determined by disability assessment based on the Barthel Index for Activities of Daily Living or other evaluation tools designed by the pilot cities [9]. In some cities (e.g., Qingdao), people with moderate or mild disabilities could also be eligible for LTC insurance benefits [9]. The benefit package varies across pilot sites. Most pilots covered a combination of home- and community-based services, institutional care services, and hospital care [9]. The type and frequency of LTC services that beneficiaries could receive depended on the severity of their disability [9]. The reimbursement rates varied by the type of LTC services provided and were typically more generous for home care [9]. Some pilots reimburse service users with a fixed percentage of the total expenditure, with or without a cap and within a specific period of time [5]. Other cities reimburse a fixed amount per day or month with limits on the total hours or days that can be billed [5]. All the pilot cities provided direct services, and Shanghai also offered some cash benefits [9]. Most cities pay service providers either on a fee-for-service or per-diem basis [5]. Since 2020, the Chinese central government has expanded the LTC insurance pilots to 49 cities [13]. After seven years of pilots, during the 20th Party Congress in 2023, the central government formulated a strategic plan to establish a unified national LTC insurance system, building upon the prior pilot experiences [10]. | |||||||||||||

| Regulation and quality assurance | In December 2020, the State Council of China issued its Opinions on the Establishment of a Comprehensive Regulatory System for LTC [14]. This policy document outlines the specific responsibilities of 16 government departments. Notably, the civil affairs department is responsible for overseeing and managing the service quality, safety, and operations of LTC providers. Additionally, it plays a facilitating role in establishing a standardized system for LTC services and conducting credit supervision of providers. Local Departments of Civil Affairs are responsible for accrediting non-profit providers, while local Industrial and Commercial Administration Departments handle the accreditation of for-profit providers. The Ministry of Civil Affairs stipulates Guidelines for the Implementation of the National Standard for the Classification and Evaluation of Long-term Care Providers [15]. Provincial Departments of Civil Affairs establish their own standards based on national guidelines and local characteristics, conducting evaluations of providers, and publishing the rating results to the public. In 2021, the central government issued Opinions to establish a randomized inspection system, accompanied with a checklist of key inspection items for LTC providers [16]. The inspection results are to be released to the public by local authorities. | |||||||||||||

| Service Delivery | ||||||||||||||

| Service Delivery Overview | The Chinese central government advocates for ‘90–7–3’ and ’90-6-4’ frameworks for LTC, envisioning that 90% of older adults receive home-based or informal care, 7% or 6% receive community care, and 3% or 4% receive institutional care. Overall, family caregiving plays a pivotal role in supporting individuals requiring care in China. According to a national representative survey, only 1.5% of older respondents exclusively received formal care services in 2020 [17]. China’s formal LTC sectors are characterised by a growing institutional care sector and an underdeveloped home- and community-based care sector [5]. Home- and community-based care services, which has a short history in China, are more accessible in provincial capitals and megacities. According to a survey in 10 major cities, approximately 13.6% of respondents received help with meals, bath, housework, or day care [18]. | |||||||||||||

| Community-based care | Over the past decade, policy initiatives aimed at accelerating the development of community-based care have been launched in major cities to test various services models (e.g., community stations). Recently, a service model in rural area, called Happiness Home, has garnered increasing attention and support. Table 2 summarises typical community-based care facilities and the type of services available in mainland China. Although the majority of older adults in China prefer home- and community-based care over institutional care, approximately 32.6% of them have not used the needed services [7]. Among those who used the services, 27.8% used housekeeping services, 22.5% used medical services such as chronic disease diagnosis and treatment, and rehabilitation care, and 20.6% used catering services [7]. The home- and community-based care sector remains underdeveloped compared to institutional care and is concentrated in urban areas [5]. In large cities, government subsidies incentivise community day care centres to establish a limited number of beds for disabled older people in need of overnight or short-term stays [5]. Developing community-based care in rural areas poses significant challenges due to inadequate resources, insufficient policy attention, and the widespread geographical dispersion of residents [5]. To enhance home- and community-based care nationwide, the central government has initiated a series of pilot programmes by providing financial assistance to local authorities since 2016 [19]. Some improvements have been observed Table 2. Typical community-based care facilities and types of services for older adults in China

Sources: Feng et al. (2020) and National Standards by the Ministry of Civil Affairs

| |||||||||||||

| Residential care settings | The primary motivation of older adults to choose institutional care is the concern about burdening their adult children, especially among those living with disabilities or dementia [7]. Nursing homes primarily offer services such as meals, bathing, personal hygiene, and health-related services like medical check-up, prescriptions, health management [7]. Many facilities also provide entertainment and leisure services, promote social participation, and offer psychological comfort services [7]. Most service users prefer facilities that are publicly operated or were previously publicly operated providers [7]. Over the past two decades, we have observed an increasing role of the private sector in institutional care provision in China [5]. Historically, institutional care for older people in China was limited to a small number of publicly supported welfare recipients [5]. In recent years, the Chinese government has introduced a series of policies aimed at encouraging the establishment of LTC facilities by the private sector, leading to the proliferation of private LTC facilities across major cities [5,17]. These facilities vary in terms of the services provided, fees charged, residents served, and the quality of care [5]. Institutional care facilities for older people can take two main forms: they can be directly owned and managed by the government or developed, owned, and operated by the private sector [17]. To engage the private sector, both national and local governments have embraced various types of public-private partnership models, whereby the government contracts with private companies to deliver a scope of services or operate a government-built facility, or sometimes a combination of both approaches [5]. Despite the fast-growing private market, private care homes tend to be less popular than government-owned ones due to their locations away from downtown areas and a lack of professional care workers to assist with functional limitations [20]. It is observed that government-owned care homes have long waiting lists, whereas some private care homes have an occupancy rate well below 50% [20]. Moreover, care home services remain unaffordable for many Chinese older persons. For instance, the median price of nursing home services in Beijing in 2020 was 5,000 RMB per month, excluding food and medical expenses, while the average pension was 4,365 RMB per month [21]. Construction and operating subsidies are available to private non-profit facilities [1]. Consequently, the majority of private providers are registered as non-profit organisations so they can qualify for government subsidies and receive tax breaks [1]. However, in practice, they might operate as for-profit services [1]. These non-profit providers are primarily small or medium-sized operations that tend to target individuals with low incomes or lower-middle incomes [1]. In contrast, for-profit providers are relatively few in numbers and tend to be large corporations that target middle-income or high-income households, offering services of relatively higher quality than non-profit providers [5]. In rural China, nursing homes (jing lao yuan) are characterised by poor conditions, limited services and amenities, a bad reputation, and persistent stigma associated with living in these facilities, which contribute to low occupancy rates [17]. Rural residents are less willing than urban residents to live in care homes [22]. Even among the target residents, older people with low incomes, disabilities, and no family support, there tends to be reluctance to admit themselves to such facilities [17]. | |||||||||||||

| Enabling environments | Recently, the central government has been committed to developing an age-friendly environment for Chinese older adults. In 2017, the State Council proposed the formulation and implementation of an aged care services programme, which emphasised the promotion of age-friendly communities. The priorities were given to renovate public facilities closely related to the daily lives of older people, provide appropriate equipment to assist older individuals with their travel needs, and support the installation of elevators in residential buildings with a high proportion of older residents [23]. Additionally, in 2019, the central government launched an age-friendly home renovation programme for older residents with financial hardship, disabilities, and other special difficulties through government subsidies [24]. Originally planned to conclude by the end of 2020, it has been extended to the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021–2025) [24,25]. The age-friendly retrofitting covers various aspects, including flooring, doors, bedrooms, toileting and bathing facilities, kitchen equipment, the physical environment, and daily living aids [25]. Moving to this year, the provision of barrier-free renovation services for households with older people facing financial difficulties has been included in the List of National Basic Aged Care Services [26]. | |||||||||||||

| Assistive technology | China has not yet established a national subsidy system for individuals with disabilities in need of assistive devices, but some local systems are in place [27]. Additionally, in 2018, the central government launched a pilot programme to lease rehabilitation assistive devices at the community level in selected cities [28]. Nonetheless, the utilisation rate of assistive devices among older adults who reported a need for the devices is low in China [29]. | |||||||||||||

| Workforce | China faces a shortage of professional LTC workforce, both in terms of numbers and skill sets. While the country has over 40 million older adults with disabilities in need of LTC, there are only an estimated 300,000 registered LTC workers [30]. The shortage of professional workforce will be exacerbated by rapid increase in the demand for long-term care and a decline in the availability of unpaid caregivers in the next few decades. Moreover, it is not solely a matter of shortage of workers in numbers but also a skills gap that leaves the current system ill-equipped to address the multifaceted needs of China’s older population. The frontline aged care workers in China are predominantly middle-aged women with limited education and training [31]. As a result, their roles are primarily limited to providing basic daily assistance such as housekeeping, meal delivery, purchasing necessities, and companionship [1]. However, they are unable to meet the requirements of those with functional and cognitive impairments, such as functional assessment, health management, and rehabilitative assistance [1]. China’s skilled LTC workers are primarily concentrated in urban residential care facilities [1]. Social workers, nurses, general practitioners, and other healthcare professionals can play a crucial role in the provision of professional LTC services for older people with complex chronic conditions, yet these roles are often inadequate. The shortage of nurses in China’s long-term care facilities is estimated to reach 600,000 [32]. Only a small proportion of residential care facilities in major cities are staffed with social workers; many of them are passionate and young with a solid theoretical knowledge base but encounter challenges in translating theory into practical skills [1]. While some urban institutional facilities have professional clinical personnel, home- and community-based care providers, as well as rural aged care homes, primarily rely on existing healthcare resources in their locality, which are often insufficient [1]. To address these challenges, the central government has primarily focused on improving care capacity through the development of professional educational programmes [33]. Over the years, the number of nationwide educational programmes directly related to LTC has surged from 86 in 2015 to 186 in 2018 [5]. Nevertheless, despite these endeavours, the sector faces a persistent issue of unattractive career prospects, including social biases against LTC workers, coupled with low wages and limited benefits, demanding working conditions, unclear pathways for career development, and generally low job satisfaction [1]. Consequently, enrolment in these programmes remains notably low [5]. Currently, the majority of care is provided by family caregivers [5]. In recently years, several policy directives have aimed to provide support for informal caregivers. One such initiative is the provision of vocational training subsidies for qualified family caregivers of older adults with disabilities who participate in nursing training and other related vocational skills training[26]. This has been included as one of the National Basic Aged Care Services by the central government [26]. During the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) period, the central government has set a policy roadmap to establish a one-child parental care leave system and to develop respite care services for family caregivers of older people with disabilities or dementia [34]. Previously, Beijing piloted a respite care programme in certain areas since 2018, where the local authority covered the expenses for up to 32 days annually [35]. Additionally, in some LTC insurance pilot cities, older people with disabilities can designate a family caregiver who, after receiving professional training, becomes eligible for a monthly allowance [36]. | |||||||||||||

| Information systems | Currently, there is no national information system for long-term care in China. However, the National Plan for the Development of the Aged Care System during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021–2025) sets a policy roadmap to develop city-level information platforms to facilitate the delivery of home- and community-based care for older adults [34]. Additionally, it stipulates the promotion of data sharing between the healthcare and LTC sectors and the improvement of the information management system for integrated healthcare and LTC services [34]. | |||||||||||||

| New models of care and innovations | Since 2015, the integration of healthcare and LTC systems has become a policy priority for the development of aged care in China [37]. In 2015, the central government issued a policy directive outlining the framework and principles for an integrated healthcare and LTC system [38]. It proposed five key areas of integration, including collaboration between medical and LTC facilities, the provision of health services in LTC facilities, encouragement of primary care providers to deliver health services in communities or at home, encouragement of social forces to establish institutions for integrated care, and the provision of health services in home- and community-based LTC settings [38]. Subsequently, a series of policy initiatives were introduced, with a shift in focus from a broad macro-level system framework to more specific micro-level guidelines [37]. Similarly, the emphasis shifted from developing service networks to formal institutional arrangements [37]. Various integration models were piloted and implemented at different levels and in various settings [39,40]. Preliminary standards were set for service delivery and management within integrated care organisations, serving as quality assurance guidelines [41,42]. To fund these services, a range of funding sources, including central government budget, were established, resulting in a significant increase in financial resources contributed by both the government and society [37,43]. By the end of 2021, a total of 6,492 institutions were qualified to deliver both healthcare and LTC services, with over 90 percent of the LTC facilities capable of providing healthcare services [37]. In June 2023, in recognition of the rising disease burden of dementia, the National Health Commission launched a nationwide campaign to promote actions for dementia prevention and treatment from 2023 to 2025 [44]. Specific measures include raising awareness, conducting cognitive functioning screening tests for all older adults aged 65 years and over, providing early intervention for those with cognitive impairment, offering training for memory clinic personnel, community centre workers, social workers, and other professionals, as well informal caregivers [44]. This initiative also aims to establish a dementia prevention and treatment service network spanning community neighbourhood committees, village committees, community health service centres, village health offices, medical facilities, disease prevention and control centres, social work service institutions, and related volunteer organisations [44]. This initiative builds upon a pilot programme for disabilities and dementia prevention introduced in selected counties of 15 pilot provinces in 2021 [45]. | |||||||||||||

| Performance | ||||||||||||||

| Availability & accessibility | After several years of piloting, by the end of 2022, the number of participants in LTC insurance had reached 169 million, with a cumulative total of 1.95 million people benefiting from the pilots [47]. The cumulative expenditure had reached 62.4 billion RMB, with an annual per capita expenditure of 14,000 RMB [47]. Concerns regarding the fiscal sustainability of the LTC insurance programmes under a pay-as-you-go framework have arisen, especially considering the increasing population ageing [17]. Furthermore, it has been reported that there were notable disparities in the financial burden experienced by enrolled participants, despite efforts to ensure equal access to LTC [48]. Given the great variations in localities’ financial resources to potentially fund the LTC insurance, it is unclear to what extent the LTC insurance schemes can be extended beyond the piloted cities and rolled out to the entire country. | |||||||||||||

| Quality of care | China lacks an overall, systematic, scientific, comparative evaluation system for the quality of LTC services [46]. Several case studies investigating the quality of residential LTC care in urban areas indicate significant variations, both geographically and across public and private sectors [17]. This heterogeneity exists because although China has established several national standards addressing safety and the quality of care in residential LTC facilities, local governments possess the flexibility to define operational standards and enforcement measures under national guidelines [5]. Unfortunately, quality regulation remains weak due to inadequate inspections and inefficient enforcement of regulations [5]. Regarding home- and community-based care services, there are no national regulation, leading to variations in the degree of regulation and LTC quality assurance based on service settings and locations [5]. | |||||||||||||

| Effectiveness | There is an emerging body of studies aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of LTC insurance pilots on healthcare and LTC access, cost, and the wellbeing of older adults. Empirical evidence suggests that the introduction of LTC insurance reduced unmet LTC needs related to activity of daily living (ADL) among older adults, as well as the probability and intensity of informal care, ADL-related care expenditures, out-of-pocket medical expenses, and hospital utilisation [9,49,50]. Additionally, the implementation of LTC insurance was associated with improved self-rated health and lower mortality risk for older people [9]. | |||||||||||||

| Lessons from the COVID pandemic | During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese government responded by implementing strict isolation policies. The restriction of movement prevented rural-to-urban migrants, who comprised a significant proportion of long-term care workforce, from returning to cities, resulting in a more severe staff shortage than ever before [48]. Moreover, strict social isolation measures heightened the difficulty for older adults with functional limitations who lived alone to obtain assistance in daily living from family members, neighbours, and friends [48]. Social isolation and loneliness are common among older adults in need of LTC, but many are not proficient in using mobile technologies, which may have further affected their mental health [48]. Residential care providers faced challenges of increased operational costs and rising vacancy rates [48]. To improve China’s LTC system, it is recommended through improving the benefit package of pilot LTCI schemes, fostering an integrated care system with the healthcare sector, facilitating better access to mobile technologies among older adults with functional limitations, and promoting people-centred care across care settings [48]. | |||||||||||||

| New reforms and policies | After the pilot experiences with LTC insurance since 2016, the central government aims to gradually develop a national LTC insurance system, as stated in the National Plan for the Development of the Aged Care System during the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) [34]. Initially, the focus will be on providing the basic care needs of severely disabled individuals covered by the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance, with financing primarily based on contributions from both employers and individuals [34]. In 2021, the central government issued a national assessment criterion for LTC disability levels to facilitate the development of this unified system, outlining the goal of harmonising the assessment criteria in the pilot cities within the subsequent two years [51]. The National Plan also set a goal to formulate a list of basic care services covered by LTC insurance [34]. In the meantime, the Chinese central government also demonstrates strong commitment in strengthening the home- and community-based care services (HCBS) in China. From 2016 to 2020, the central government selected five cohorts consisting of 203 pilot sites and provided financial assistance to local authorities for their initiatives to improve the HCBS [52]. Local authorities at pilot sites implemented a variety of measures, such as enhancing the availability of community-based canteens for older people in rural areas, increasing the provision of bathing services, developing innovative institutional mechanisms for the government purchase of private HCBS services for local older residents, promoting the development of respite care for informal caregivers of older people living with functional disabilities or dementia, exploring the use of digital devices to facilitate the provision of HCBS, expanding professional services from nursing homes to older people’s homes, developing a professional workforce, and promoting ageing-friendly housing adaptations [52]. During the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021–2025), the Chinese central government committed to further promoting HCBS [34]. The Ministries of Civil Affairs and Finance launched successive rounds of the HCBS pilot programme from 2021 up to now, providing subsidies for constructing home care beds or developing home care services for financially disadvantaged and functionally disabled older adults [53]. In addition, the central government has outlined several policy directives as key tasks to accomplish during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021–2025). These directives include the establishment of a system for basic aged care services, strengthening the role of public nursing homes for older adults as a safety net, accelerating the development of LTC in rural areas, and improving health services in LTC settings (e.g., health education, geriatric care, rehabilitation, hospice care etc) [34]. | |||||||||||||

| Suggested Citation | Ping, R. and Hu, B. (2024) Long-term care system profile: mainland China. Global Observatory of Long-Term Care, Care Policy & Evaluation Centre, London School of Economics and Political Science. https://goltc.org/system-profile/china-mainland/ | |||||||||||||

| Key Sources | Glinskaya E. Feng Z. Options for aged care in China: Building an efficient and sustainable aged care system. World Bank; 2018 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1075-6 Feng, Z., Glinskaya, E., Chen, H., Gong, S., Qiu, Y., Xu, J., & Yip, W. (2020). Long-term care system for older adults in China: policy landscape, challenges, and future prospects. The Lancet, 396(10259), 1362-1372. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32136-X Chen X, Giles J, Yao Y, Yip W, Meng Q, Berkman L, Chen H, Chen X, Feng J, Feng Z, Glinskaya E. The path to healthy ageing in China: a Peking University–Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 2022 Dec 3;400(10367):1967-2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01546-X | |||||||||||||

| References |

| |||||||||||||

KEYWORDS / CATEGORIES | ||||||||||||||

| Countries | China | |||||||||||||