By Vayda Megannon, Elena Moore and Zeenat Samodien (The Family Caregiving Programme – University of Cape Town)

South Africa’s policy orientation towards older persons is shaped by the principle of “ageing in place”. This approach, enshrined in the Older Persons Act (2006), assumes that older adults will remain in their homes and communities, supported by family members and supplemented by limited community-level services. While attractive in principle, the reality of ageing in place is markedly different in contexts where poverty, underdeveloped infrastructure, and limited state provision define daily life. Family care for older persons is the most prevalent form of long-term care in South Africa and yet there is little evidence on how it happens. This blog shares some of the main findings from our exploration of family care of older persons.

The Family Caregiving Programme’s recent study, undertaken across seven sites in the Western Cape, Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces, engaged with 96 older persons and 103 family caregivers to explore the lived dynamics of elder care. In the report, the findings reveal that although most older persons do receive some form of care, this is overwhelmingly provided by daughters and female kin in conditions of material scarcity. Far from representing a benign preference for family-based care, ageing in place in South Africa often entails the transfer of responsibility from the state to the household, with considerable costs borne by women and their families.

Configurations of Family Care

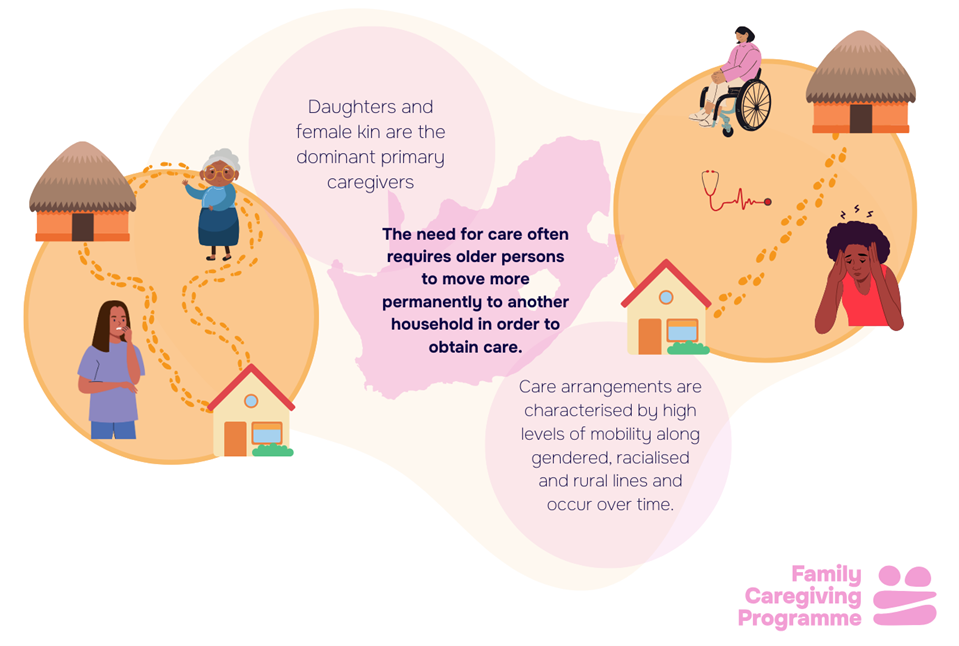

The dominant model of care provision is co-residential care, most often undertaken by daughters who were already resident in the household or who relocated in order to provide care. Households are typically large, multigenerational, and characterized by multiple, competing care responsibilities, including childcare.

Care arrangements are highly dynamic. Approximately one in five caregivers moved to provide care, while more than one in ten older persons relocated to a caregiver’s household. These movements are rarely straightforward. They involve significant financial expenditure, disruption to household routines, and considerable emotional labour. In cases where adult children were absent due to death, migration, or other factors, nieces, neighbors and adult grandchildren frequently assumed caregiving responsibilities. This fluidity underscores the porous and negotiated character of kinship in South Africa, where the boundaries of “family” are defined as much by obligations of care as by biological ties.

The Labour of Ageing in Place

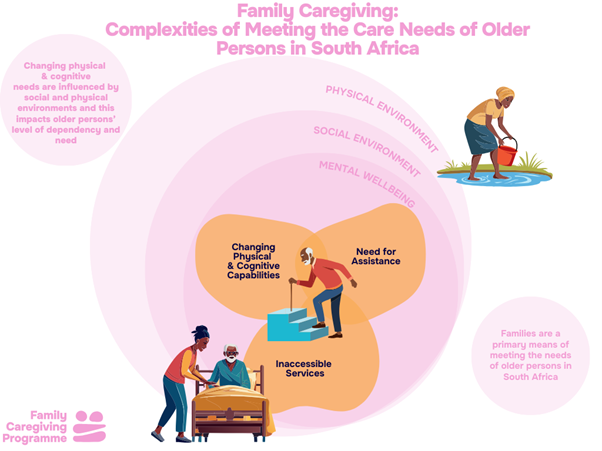

Elder care cannot be understood solely in terms of health status. Instead, the built environment profoundly shapes both the extent of older persons’ needs and the labour required of caregivers. Many households lack ramps, indoor plumbing, safe sanitation, and accessible transport. As a result, tasks such as bathing, mobility support, or collecting medication are rendered arduous and time intensive.

Survey data show that one in five older persons struggle with at least one activity of daily living, while life expectancy estimates indicate that many South Africans will live five to six years beyond 60 in poor health. Given that most people do not have medical insurance and community-based services remains limited, these care needs fall almost entirely to (female and extended) family members.

Caregiving in these contexts is physically and emotionally depleting. Over one-third of caregivers were simultaneously caring for children; one quarter of women in the sample had left employment or ceased job-seeking to provide care; and a third of caregivers themselves lived with chronic illness or disability. Emotional labour (supporting older people who experience pain, grief or loneliness) compounds these pressures, particularly with complex or difficult relational histories.

The Financial Architecture of Care

Care is always embedded in material conditions, and this is true for across the Southern African region. In South Africa, black older-person households, particularly in rural KwaZulu-Natal and Eastern Cape Provinces, were found to have the lowest average incomes (approximately R4800/ £200 per month) despite large household sizes. Food absorbs around 60% of monthly household income, yet the cost of a nutritious diet for family of five (R4459/ £620 in July 2023) far exceeds what is affordable. The findings show that debt repayments account for a further 18-38% of income, while transport consumes 6-15%, with the burden particularly acute in rural households.

The costs of elder-specific care items further destabilases household budgets. Adult incontinence products, inconsistently supplied by public clinics, cost between R1000 and R1600 (£43-£70) per month if made to purchase privately – an impossible figure for most households. Transport barriers further prevent older persons from accessing clinics or social services, forcing caregivers to assume these responsibilities. In the absence of accessible infrastructure, the work of care expands dramatically.

Families adopt coping strategies that are stressful, expensive, non-nutritious and unsustainable: reducing food intake, prioritizing starch over nutrition, borrowing from informal lenders, and foregoing medical visits. Older persons often remain central decision-makers in household finances, responsible for stretching grants and managing trade-offs. This frequently produces intergenerational tensions, with caregivers expressing guilt over limited contributions (between and within households and family members) and older persons voicing frustration at not being able to meet their own care needs.

Challenging Persistent Assumptions

The study’s findings challenge several enduring assumptions. The presence of family in the household does not necessarily ensure that care needs are met, as family members are not always physically able, available, or sufficiently supported to provide adequate care. Contrary to the perception that residential care is exclusively for white and high-income families, many black older persons and caregivers expressed openness to alternatives when circumstances make home-based care unsustainable, although access remains shaped by apartheid-era infrastructure and service distribution. Similarly, the assumption that ageing in place is a cost-effective solution for the state overlooks the reality that it is only rendered “affordable” by offloading the financial, emotional, and physical costs onto women in low-income households.

Recommendations for Policy and Practice

Caregivers and resources (time, energy etc) are not an endless supply of labour, or care. In this way family care for older persons needs to be better supported. We propose three key strategies to recognise, redistribute, and reduce the care burden on older persons and their family caregivers.

- First, we advocate for the introduction of a ‘caregiver grant’ or some form of compensation to acknowledge and recognise the vital work caregivers perform.

- Second, we emphasise the importance of accessible home-based care services, which are essential for redistributing the care load, offering respite, and supporting the mental health of family caregivers.

- Third, we want to reduce the care load, and highlight the need for improved access to incontinence products, reliable medication delivery for those with high care needs, and nutritious food. These practical supports would significantly lessen the caregiving burden, as family caregivers currently devote considerable time to laundry, medication collection, and ensuring adequate nutrition in resource-constrained settings.

The historical geography of elder care in South Africa cannot be ignored. Apartheid and colonial policies directed resources toward white urban centers, building residential facilities and services that remain disproportionally accessible to white populations. Meanwhile, black rural and township communities continue to content with inadequate infrastructure and chronic underfunding.

The result is that ageing in place is, for the majority, not accompanied by meaningful support but by intensified dependence on unpaid female kin. Family resilience has sustained older persons thus far, but resilience is not a sustainable policy model. As the population ages, the fragility of this arrangement will only become more apparent.

The vision of ageing in place is not inherently flawed, but in South Africa it currently translates into ageing with unpaid family care, depleted household resources, and inadequate state support. The sustainability of this model is in question. To ensure dignity in later life, elder care policy must move beyond rhetorical reliance on families and actively invest in redistributive systems of support. Without such intervention, ageing in place risks becoming less a policy aspiration than a euphemism for prevised, gendered, and inequitable care.